PÚBLICO

Design Research

TypeAlejandra Hernandez, Juan David Sánchez

CollaboratorsCajicá, Colombia

Location2020 - Ongoing

Year In the last few decades, we have witnessed the expansion of urbanization across the globe. Contrary to the promise of amelioration of living conditions that urban migration once represented, cities' living conditions deteriorate at an increasing rate for large segments of urban populations. As traditional urban planning and architectural practices seem to fail in the face of gentrification processes, community displacements, growth of informal settlements, and degradation of ecological systems; it is possible to re-establish self-governing operations that are ruled by communal welfare rather than the economic interests of a few?

PÚBLICO is a physical space in Cajicá (Colombia), offering an independent place from where local people and groups can participate in the construction of the environments that surround them. The project questions established city-making practices by creating a setting for citizens to become active agents in reshaping their city through the development and support of community-led endeavours.

PÚBLICO invites citizens to use its space for talks, activities, discussions, film screenings, exhibitions, walks, concerts, installations, classes, performances to create discussions around what it means to inhabit Cajicá. Operating as a place of exchanges between users, viewers, and occupiers, PÚBLICO makes city-making practices accessible to a broader range of people while diversifying the agents involved in the city's production. Instead of letting a few experts planning the future in the name of others, PÚBLICO proposes a scheme where collective interests and well-being drive the design and construction of our built and natural environments.

PÚBLICO is a physical space in Cajicá (Colombia), offering an independent place from where local people and groups can participate in the construction of the environments that surround them. The project questions established city-making practices by creating a setting for citizens to become active agents in reshaping their city through the development and support of community-led endeavours.

PÚBLICO invites citizens to use its space for talks, activities, discussions, film screenings, exhibitions, walks, concerts, installations, classes, performances to create discussions around what it means to inhabit Cajicá. Operating as a place of exchanges between users, viewers, and occupiers, PÚBLICO makes city-making practices accessible to a broader range of people while diversifying the agents involved in the city's production. Instead of letting a few experts planning the future in the name of others, PÚBLICO proposes a scheme where collective interests and well-being drive the design and construction of our built and natural environments.

COMMUNAL SPACE

PÚBLICO is located in a historic house in the center of Cajicá. Before being transformed into PÚBLICO, the space was a storage room and an ice cream shop. In August 2020, after the Cavelier family lent the space to us, we cleaned and organized the room. With the help of Luis Alvarado, we painted the walls, restored the windows, opened the garden door, and repaired the tables and chairs.

PÚBLICO is designed as a 24 sqm flexible space. It is organized so it can accommodate different programs and activities. Its tables can group to create spaces for discussion or to host dinners. Its chairs become places to sit or to make an improvised stage to give a speech. Its walls are white spaces to present and project ideas or spaces to hang exhibitions and maps. The garden outside is a space to exercise or to attend a workshop on urban agriculture.

CAJICÁ, Colombia

Cajicá is a town north of Bogotá, the capital of Colombia. As part of the Cundiboyacense savannah, Cajicá sits on a privileged territory surrounded by water and mountains at an altitude of two thousand five hundred (2500) meters above sea level. To the west, Cajicá limits with the Río Bogotá, to the south with the Río Frío, and the east with la Cumbre and Montepincio (a mountainous formation part of the Andes). According to the Colombian Institute of geography, this combination of flatness, water and mountains create one of the country's most fertile soils.[1]

The Muiscas, the first recorded inhabitants of this territory, built a small settlement in the mountain's outskirt and named it: Cajicá (which means stone fortress in Muisca). They based their economy on the plantation and trading of corn. From pre-colonial times until very recent years, Cajicá was a small rural town whose cultural identity was attached to its rich and fertile agricultural fields. The water from the Rio Grande basin irrigated these lands with a natural system of streams and canals. Due to this landscape's flatness, the river naturally flooded during the rainy season, enriching and fertilizing the adjacent fields. Cajicá's cultural identity and memory were attached to its rich hydrology and fertile agricultural land.

The production of corn, potatoes, cabbage, broccoli, peas, beans, onions, and lettuce shaped the life of local communities. Mr. Benjamin Palacios (a former city councilor, actor, and community leader) remembers Cajicá as a "very safe and very peaceful place, where a lot of brotherhood existed between families."[2]Where, as Mrs. Edilma Nieto recalls, the different communities came together to help each other out and to raise money to build community spaces and buildings: "The cemetery was renovated thanks to the help of the community that organized bazaars, dances, and discos for young people. People joined and raised money and did things for the community."[3]

In the last decades, Cajicá has faced a fast-paced urban transformation. During this time, the town saw its population more than double while losing more than half of its agricultural and environmentally protected areas and seeing the construction of vertical ghettos and questionable private developments. The strong sense of identity, belonging, and citizenship that once existed in Cajicá is fading as traditional agricultural practices have disappeared, collective memories blur, and the rural vanishes. As wealthy and powerful developers shape the urbanization process by building gated communities and apartment blocks, local communities lose power in constructing their city.

In his book, Capital Cities, geographer Samuel Stein claims that the commodification of land as a highly valued asset has given real estate capital the power to shape our urban environments, politics, and, therefore, our lives[4]. In most cities around the world, new developments are the motivated ideas of private developers and landowners to profit over land. Many of these developments are not what local communities want or need, but what is more profitable for the real estate market.

This is the site and situation that initiated the creation of PÚBLICO. A site where social inequalities are highly present through spatial disparities and where local communities have lost any participation in the design and construction of the environments surrounding them. Instead of letting a few experts planning the future in the name of others, PÚBLICO proposes a scheme where collective interests and well-being drive the design and construction of our built and natural environments. Operating as a place of exchanges between users, viewers, and occupiers, PÚBLICO makes city-making practices accessible to a broader range of people while diversifying the agents involved in the city's production.

Gated communites in Cajicá.

COMMUNITY GARDEN

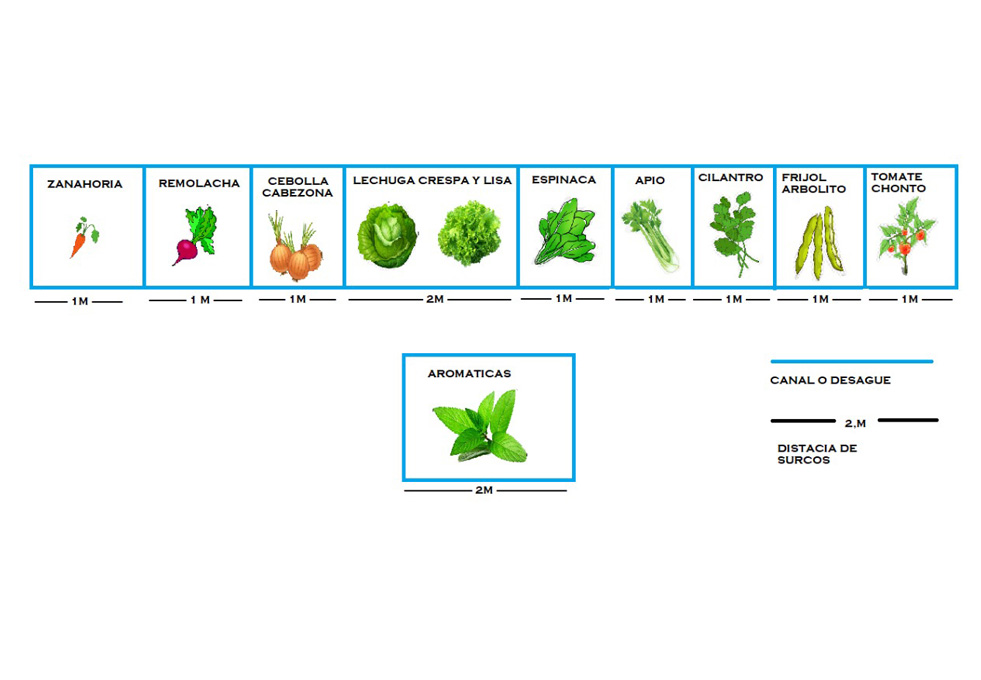

The garden started as a community-led and generated project to test a new model to support the town's food production and security by creating multiple community gardens around Cajicá. The garden at PÚBLICO is the first garden of many to come where the town's communities develop a network of spaces to share food among the most in need.

Process and construction of the community Garden

The garden in PÚBLICO is managed and maintained by Alejandra and Juan David. They have been collecting seeds from the community and planting them to preserve local agricultural products. They collected the first harvest in late December 2020 and shared all the products with community members who have been struggling to secure food due to the economic crisis caused by COVID-19. For example, the first harvest of carrots and beets was used to make a carrot cake and a beet salad, which Alejandra and Juan David shared with the community.

Taking care, harvesting and sharing

Through workshops the group in charge of the garden wants to expand the project. As they gather all the experience of creating the garden in PÚBLICO, they want to use these to make an exchange of good practices between PÚBLICO and Cajiqueños to reproduce the garden in spaces around Cajicá. The project's final product will be the creation of a handbook with simple instructions on how to create and maintain a community garden and share all of this knowledge with many communities in Cajicá and Colombia.

[1] Instituto Geográfico Agustín Codazzi, “¿En dónde están los mejores suelos para cultivar en el país?”

[2] Palacios, interview.

[3] Nieto, interview.

[4] Stein, Capital Cities, 5.